Is training harder making you weaker?

Take-aways

Training closer to RPE 10 resulted in worse strength gains than training closer to RPEs of 4-9.

Training closer to failure is unlikely to make you stronger. Prioritize heavy loads (sets of 1-5), but stay at least a rep or two shy of failure. You can train up to 6-8 reps from failure and still see robust strength gains.

Physiologically, there was no effect of training closer to failure on fatigue.

Psychologically, training closer to failure appears to initially result in more soreness, worse perceived recovery and harder sessions. However, by the end of the study, participants acclimated and these effects tapered off completely. Other data has differing findings, making it difficult to come to confident conclusions just yet.

We’ve previously covered how close to failure you should train to maximise muscle growth. To make a long story short, as you train closer to failure, a set likely becomes more effective for muscle growth, though it potentially also causes additional fatigue.

However, what about strength? Should you be taking sets to failure to maximise strength improvements?

Today, we’re reviewing a recent pre-print by Robinson and colleagues. This study sought to examine the relationship between proximity-to-failure during training and muscle growth and strength gains.

Specifically, here’s what they did. Participants were assigned to one of four groups. All groups performed the same sets/reps; the only differences were how close to failure they trained and, therefore, what weight/% 1RM they used.

The first group trained with 4-6 repetitions in the tank on all sets (4-6 RPE). The second group trained with 1-3 repetitions in the tank (7-9 RPE). The third group also trained with 1-3 repetitions in the tank, but took the last set of every exercise to failure (7-9+ RPE). Finally, the fourth group took every set to concentric failure (10 RPE).

The authors measured bar velocity during all sets to cross-validate and make sure participants were actually training as close to failure as the authors intended. All groups achieved this, except for the 4-6RPE group, which actually trained closer to 8 repetitions from failure, most of the time - even more submaximally than intended!

All groups performed a varied training routine, consisting of squats, bench press and a few muscle growth exercises (shoulder press, lateral raises, pulldown, curls and tricep extensions). While RPE was modified as described above for the squat and bench press, the muscle growth exercises were all trained at 2 repetitions in the tank for all groups.

A variety of measurements were taken before, during and after the study. First, while the authors assessed muscle thickness of the quadriceps and pecs, the measurements were too noisy to tell much. So, we’ll look past those.

They also measured 1-rep-max in the squat and bench press. Finally, they took some measurements of fatigue. Specifically, they measured creatine kinase & lactate dehydrogenase - two physiological markers of fatigue. They also measured muscle soreness, session difficulty (sRPE) motivation to train (MTT) and perception of recovery (PRS).

Let’s get into the results.

Changes in strength pre- to post-study in each group.

Improvements in both squat and bench press strength were generally greatest in the 4-6 RPE and 7-9 RPE groups. The groups training closer to failure made worse gains.

Changes in Creatine Kinase/Lactate Dehydrogenase across the study in each group.

Broadly speaking, there were no differences between groups in either marker of muscle damage. Importantly, there also didn’t seem to be much evidence of acclimation/the repeated bout effect: physiologically, similar muscle damage appeared to occur whether it was their first time doing the training session or they’d already been doing the same session for 6 weeks.

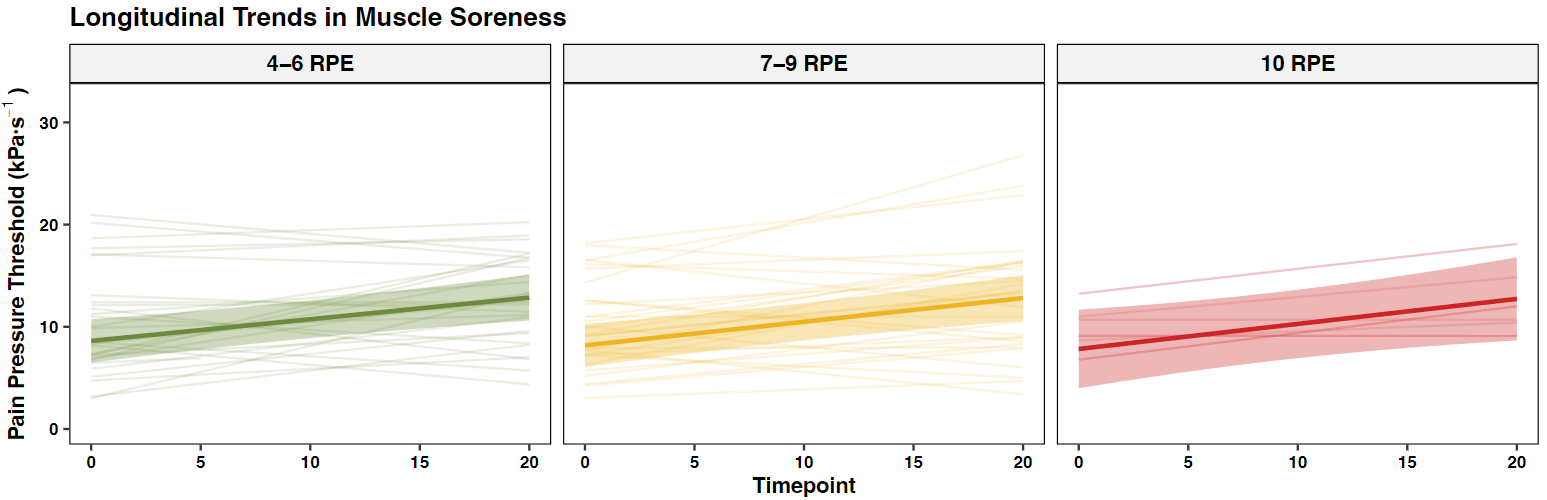

While the 10 RPE group initially saw greater soreness than the groups training further from failure, all groups appeared to experience less soreness as the study went on.

A higher score on the PRS scale indicates better recovery. A higher score on the MTT scale indicates better motivation to train. A higher score on the sRPE scale indicates a harder session.

Broadly, the PRS and sRPE scores indicate that while participants in the 10 RPE group found the sessions harder to complete and more fatiguing compared to the other groups initially, this attenuated with time.

Why?

Let’s get the strength results out of the way first. When the same sets/reps are performed, it seems training closer to failure results in markedly worse strength improvements (i.e. 2-9RPE vs 10RPE or 1-8 reps in the tank vs 0 reps in the tank). This was despite the participants in the higher RPE groups using more weight on the bar, which consistently improves 1-rep-max gains. The finding that training closer to failure is no better for strength is actually in line with a previous meta-analysis that found no benefits to training closer to failure for strength. But why? Well, it may have to do with force drop-off during a set. When you train closer to failure, you experience intra-set fatigue. Each rep tires you out, leading your force output to continuously drop. By the time you get to that last rep, your force output will be substantially lower than it would be if you were fresh. A 1-repetition-maximum/maxing out, by definition, requires you to output maximum force. Because training closer to failure involves you training in a way that is less specific, this appears to lead to worse strength gains.

To me, the fatigue/recovery results are actually the more interesting bit. Physiologically, there was no major effect of training closer to failure on fatigue (though it would be nice to have performance data, too). This is in contrast to most prior literature. Psychologically, it seems that while participants in the RPE 10 group had a harder time (in terms of session difficulty, perceived recovery and soreness) at the start of the study, by the end of the study, they were experiencing the same physiological and psychological fatigue as the other groups. This does contrast with some more recent data by Refalo et al., making it hard to draw firm conclusions on the topic.

If you’d like to chat about this study, feel free to comment below.

If you’re looking for an expert to handle your training and nutrition for you, check out our coaching services.