The Evidence-Based Contest Prep Guide: How to Stick to It

Competing in bodybuilding involves restricting your calorie intake and increasing your energy expenditure to lose as much bodyfat as possible. Simultaneously, you’ll be doing hypertrophy training to minimize muscle mass loss or even gain some. The high amounts of NEAT coupled with a low bodyfat level and a chronic energy deficit means your training will likely need to be different from what you would usually do. The biggest issue you’ll encounter is an increased injury risk. A major secondary issue is a reduction in motivation to train. Adherence to training is paramount for retaining lean mass as you diet. To maximise adherence, try incorporating behaviour change strategies like implementation intentions, coping plans, tracking your habits, cueing and manipulating barriers to behaviour.

This post is the second in a series of posts on how to prepare for a bodybuilding contest. Other topics covered will most likely include nutrition, supplementation, peaking strategies and posing. You can find part 1 (training during contest prep) here!

While psychological concepts like motivation can impact behaviour/habits, for the sake of brevity and applicability, I’ll try to focus on a few practical strategies to increase training adherence as much as possible. Apply these strategies and you maximize your chances of adhering to behaviour like executing a training program or sticking to your cardio.

Implementation Intentions

First up is something called an implementation intention (1). It’s a statement of your intention to implement or perform a certain behaviour. The act of writing it down can increase its effectiveness. Here’s an example;

“I will train everyday.”

Now, while the above sentence is a start, we can do better. It seems like being more specific with the circumstances under which we plan on performing the behaviour helps. Adding in time and location is helpful.

“I will train everyday at my local gym at 5PM.”

This is already better! If you don’t feel confident in setting a specific time for the habit, you can try scheduling it for after you perform another regular habit. This is sometimes called habit stacking:

“I will train everyday at my local gym after I go for my daily walk.”

Implementation intentions can be particularly powerful when combined with a calendar app. Even the simple act of scheduling your training can increase the likelihood that you’ll go through with it. You can think of it the same way you would writing down an implementation intention on paper. Furthermore, on a calendar app, you can set reminders, which further helps you stick to your habits.

Coping Plans

In addition to implementation intentions, there is a technique called “coping plans” (2). Now, as the name suggests, coping plans are plans you make for coping when things don’t go according to plan. For example, let’s say you’ve resolved yourself to train everyday at the local gym after your daily walk.

Monday, Tuesday & Wednesday, you stick to this habit. You’re doing great! However, as you’re on your walk on Thursday morning, it starts raining. You get drenched and need to go home. By the time you get home, you’ve resigned yourself to skipping training.

Here’s where coping plans come in. An example:

“If the weather forecast suggests it’ll rain when I go for my walk, I’ll take an umbrella with me.”

The structure of a coping plan is essentially “If [undesirable external circumstance] happens, I’ll [do something to stick to my desired habit/behaviour].”

You can also use this for going off diet. Here’s an example:

“If I go off plan and have a cheat meal, I’ll simply get back on my meal plan for the next one and carry on from there.”

Track your training

Tracking/monitoring your behaviour can be a powerful tool for encouraging behaviour and habit formation. Simply put, find a way to track your training.

A common tool to use for this (and the one I use) is a habit tracker. It can be as simple as just a spreadsheet with columns for each day and rows for each habit you want to stick to. My habit tracker, for example, includes a row for “12K steps” – doing 12 000 steps on any given day – and a row for “Train” – doing the training I was supposed to do.

I’ve been tracking habits for a few years now and I’ve found it quite useful in both getting an overview of how well I’m adhering to a desired habit and encouraging further behaviour.

Cueing

Cueing essentially refers to designing your environment to encourage a certain behaviour. Let me explain through an example.

Let’s say you want to start training again. To do so, you’ll need to bring your training shoes, a towel and a water bottle. If you take those out from where they are currently stored and place them in plain sight and in a convenient location (e.g. next to the door leading outside of the house), you’ll encourage the behaviour of training. You’ll encourage it both by reminding yourself of your desire to commit to training and by facilitating the behaviour (when pressed for time, for example, it’s easier to go train when all your stuff is ready to go by the door).

Another example of cueing could be the reminders you set for training on your calendar app. By setting those reminders, you’ve changed your environment to remind you of your desire to train at a certain time.

Manipulate barriers to behaviour

Finally, manipulating barriers to behaviour can also be a useful strategy. This one will also need to be individualized.

Let’s say you’re trying to lose some fat. You want to eat less calorie dense food to help with hunger. You decide some white rice would be something that you’d enjoy and that would help satiate you. However, you realize that cooking white rice takes time – time that you don’t have.

The barrier to a desired behaviour here (i.e. eating white rice) is the lack of time. There are a few different options to remove this behaviour. You could buy a rice cooker, which would save you time and allow you to eat white rice. You could buy microwavable rice, which also saves you time and would encourage the habit of eating white rice.

Ask yourself what the barriers to desired behaviour are. Then, however small the barriers are, try thinking of ways to remove those barriers and make the desired habit as easy as possible to stick to.

It’s also worth understanding that you can flip this technique; make the behaviours that are undesirable HARD to do. For instance, if you want to stick to your diet, an easy way to make it less likely that you’ll “cheat” is by removing all non-diet foods from your home. This makes the behaviour of cheating on your diet harder by requiring you to go buy non-diet foods before you can eat them.

Putting it all into practice

Here are some examples of how to use these strategies specifically for sticking to training and cardio during contest prep. Some techniques work better for certain habits, but, by and large, most techniques can work for most behaviours.

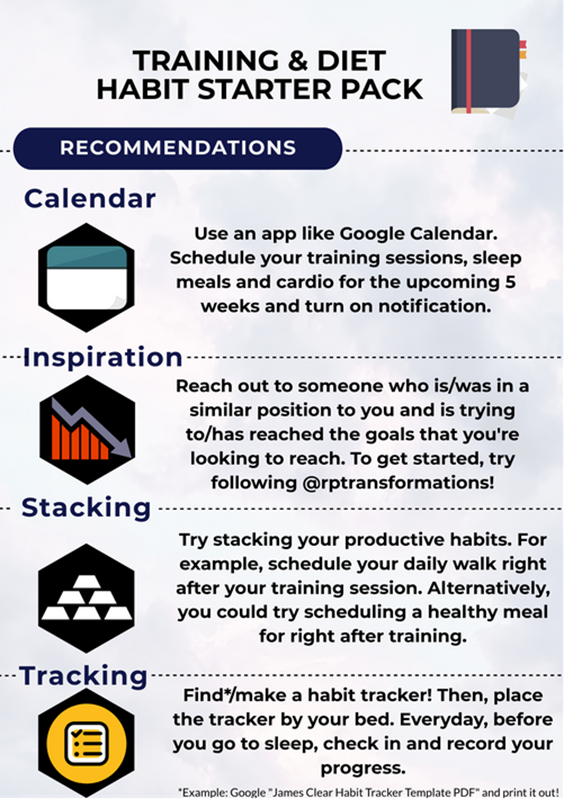

Here are a few infographics I made a while back that summarize some of the more common behaviour change techniques:

A lot of the information from this post was inspired/taken from Atomic Habits by James Clear. If you’re interested in taking control of your habits, I highly recommend you check it out!

1. Da Silva, M. A. V., São-João, T. M., Brizon, V. C., Franco, D. H. & Mialhe, F. L. Impact of implementation intentions on physical activity practice in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One 13, 1–15 (2018).

2. Sniehotta, F. F., Scholz, U. & Schwarzer, R. Action plans and coping plans for physical exercise: A longitudinal intervention study in cardiac rehabilitation. Br. J. Health Psychol. 11, 23–37 (2006).